It's well known that stressing pepper plants by reducing watering can result in hotter peppers, and that this comes at the cost of decreased yields. But what level of stress is optimal? And which varieties respond best?

A fairly recent article in Food Science, looked into the influence of water stress in four varieties of C. chinense, by comparing the differences in yields and capascinoid concentrations in peppers watered daily or every 2, 3, or 4 days, to determine how to get the most capscacinoids out of a pepper plant.

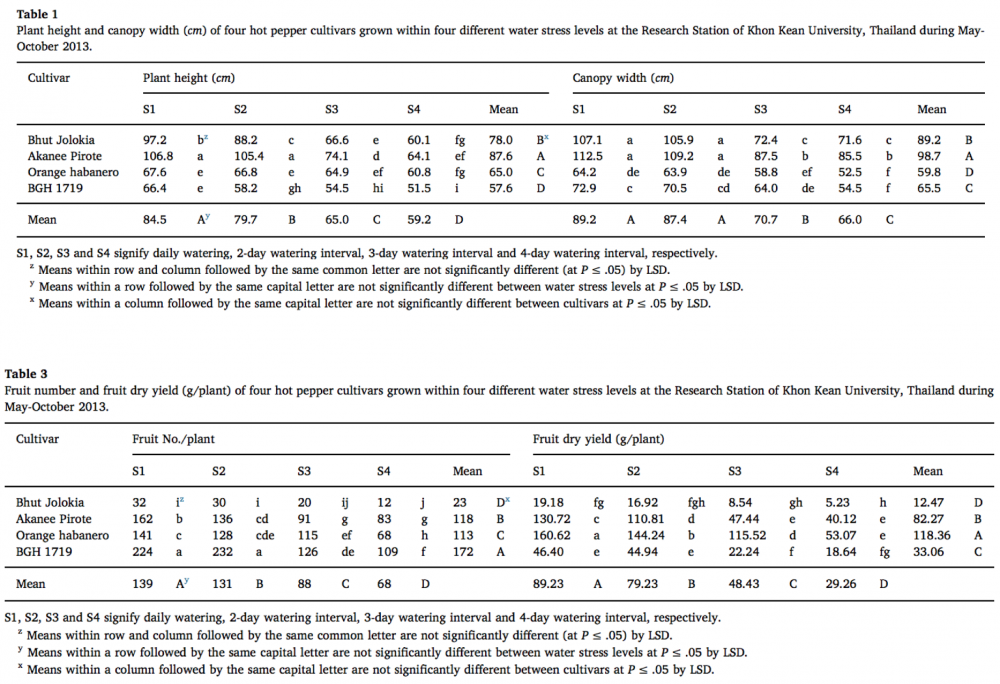

The varieties included Bhut Jolokia, Orange Habanero, BGH1719 (a smallish plant, with many small pods), and Akanee Pirote (the largest plant, with large pods around 350k)

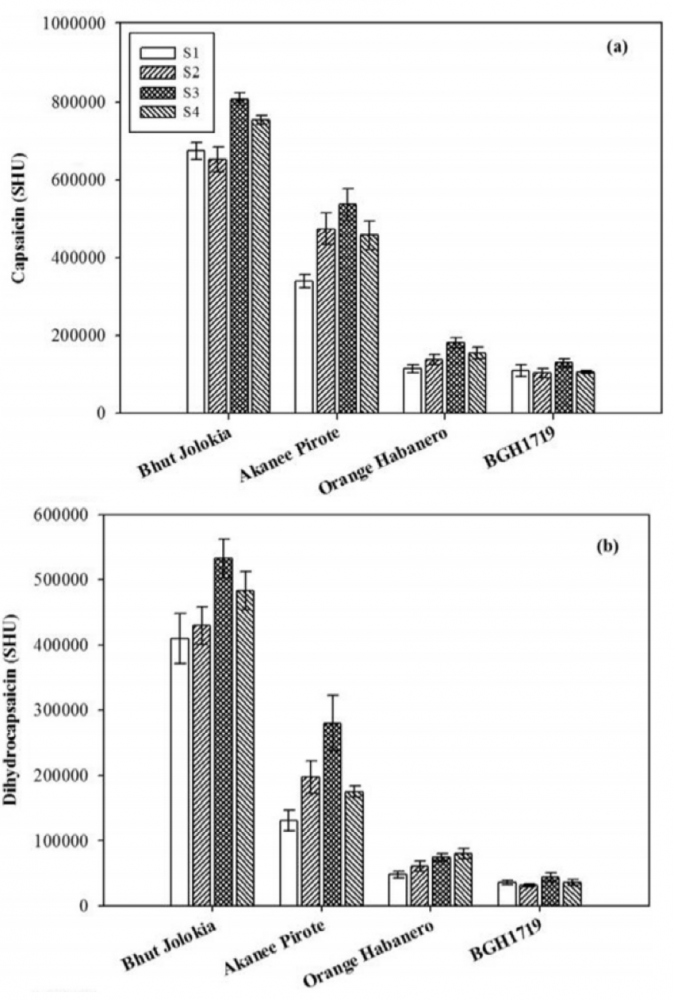

It was concluded that varieties that are hotter and have larger fruit are more sensitive to drought stresses and that mild stresses may have the potential to significantly increase capscacin in some varieties, but not others. The Akanee produced significantly more capascin in the milder 2-day stress group (from around 350k to 450k), whereas the Bhut Jolokia and Orange Habanero produced significantly more only in the 3-day stress group. Moreover, it appeared there were diminishing returns, with the 4-day group, capsacin levels were no higher (or even lower) than in the 3-day group, and plant yields continued to decline.

Looking at the specific capsacinoids, it appears that dihydrocapsacin (which is typically found in larger proportion in C. pubescens) might increase to a greater extent than capascin. So your stressed peppers might not only have a hotter burn, but a different burn.

So how might we use this information to inform our own growing practices?

Perhaps by aiming to achieve the same reduction in plant height and pod numbers, you can determine how much water stress is optimal for your climate. The data is there for Bhut Jolokias and Orange Habs, but it could potentially be generalised to other varieties. For example, the unstressed Bhut was around 1m (3ft) and yielded 32 pods, where the hotter one was ~65cm/2ft tall, with 20 pods (that's about a 1/3 reduction). A potential experiment to determine the water stress you need to apply might be to have two plants (at least), and apply stress to one, aiming for a 1/3 reduction in growth compared to the other. Then adjust in future seasons depending on how far off you were from that goal.

TL;DR: Stress your larger superhots for hotter peppers, but maybe don't bother with your small milder peppers, it might only just decrease your yields. Also, drought stress has diminishing returns, so don't torture your peppers too much!

References: Jeeatid N, Techawongstien S, Suriharn B, Chanthai. S, Bosland P. Influence of water stresses on capsaicinoid production in hot pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) cultivars with different pungency levels. Food Chemistry [serial online]. April 1, 2018;245:792-797. Available from: FSTA - Food Science and Technology Abstracts, Ipswich, MA. Accessed July 18, 2018.

A fairly recent article in Food Science, looked into the influence of water stress in four varieties of C. chinense, by comparing the differences in yields and capascinoid concentrations in peppers watered daily or every 2, 3, or 4 days, to determine how to get the most capscacinoids out of a pepper plant.

The varieties included Bhut Jolokia, Orange Habanero, BGH1719 (a smallish plant, with many small pods), and Akanee Pirote (the largest plant, with large pods around 350k)

It was concluded that varieties that are hotter and have larger fruit are more sensitive to drought stresses and that mild stresses may have the potential to significantly increase capscacin in some varieties, but not others. The Akanee produced significantly more capascin in the milder 2-day stress group (from around 350k to 450k), whereas the Bhut Jolokia and Orange Habanero produced significantly more only in the 3-day stress group. Moreover, it appeared there were diminishing returns, with the 4-day group, capsacin levels were no higher (or even lower) than in the 3-day group, and plant yields continued to decline.

Looking at the specific capsacinoids, it appears that dihydrocapsacin (which is typically found in larger proportion in C. pubescens) might increase to a greater extent than capascin. So your stressed peppers might not only have a hotter burn, but a different burn.

So how might we use this information to inform our own growing practices?

Perhaps by aiming to achieve the same reduction in plant height and pod numbers, you can determine how much water stress is optimal for your climate. The data is there for Bhut Jolokias and Orange Habs, but it could potentially be generalised to other varieties. For example, the unstressed Bhut was around 1m (3ft) and yielded 32 pods, where the hotter one was ~65cm/2ft tall, with 20 pods (that's about a 1/3 reduction). A potential experiment to determine the water stress you need to apply might be to have two plants (at least), and apply stress to one, aiming for a 1/3 reduction in growth compared to the other. Then adjust in future seasons depending on how far off you were from that goal.

TL;DR: Stress your larger superhots for hotter peppers, but maybe don't bother with your small milder peppers, it might only just decrease your yields. Also, drought stress has diminishing returns, so don't torture your peppers too much!

References: Jeeatid N, Techawongstien S, Suriharn B, Chanthai. S, Bosland P. Influence of water stresses on capsaicinoid production in hot pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) cultivars with different pungency levels. Food Chemistry [serial online]. April 1, 2018;245:792-797. Available from: FSTA - Food Science and Technology Abstracts, Ipswich, MA. Accessed July 18, 2018.